|

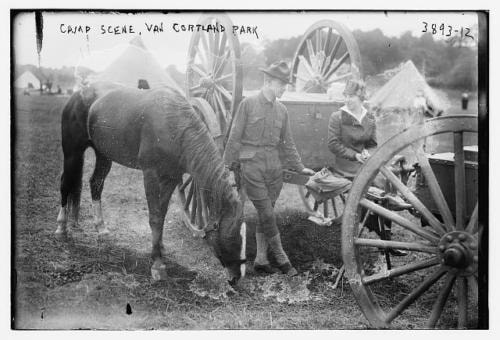

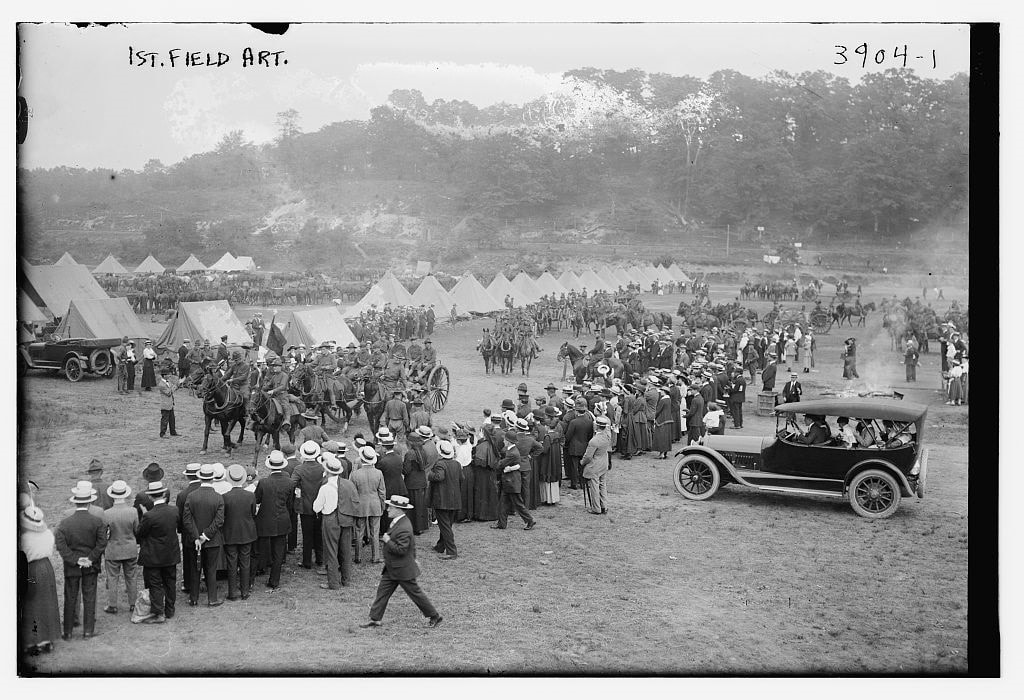

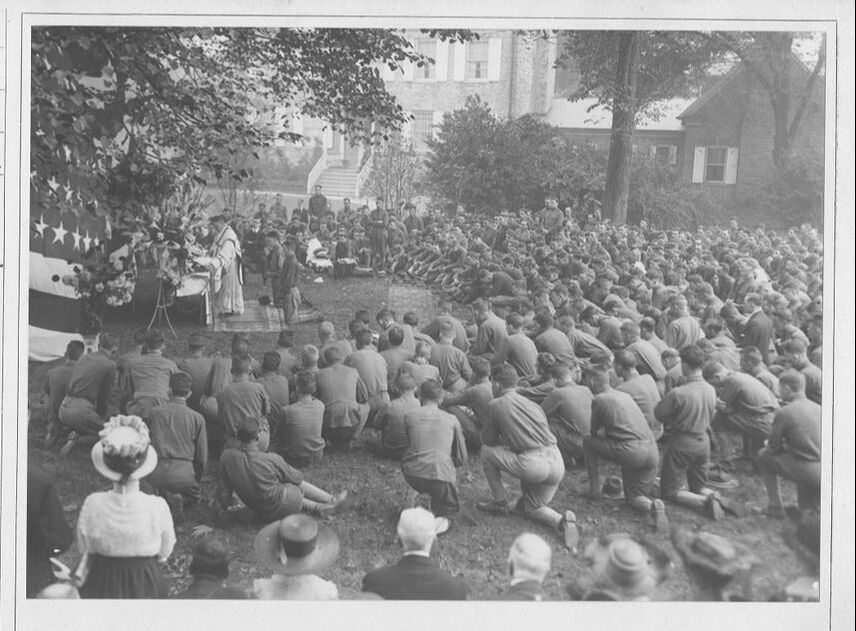

This blog post was contributed by guest author Vivian Davis who has extensively studied the 20th century military history that unfolded on the Parade Ground in Van Cortlandt Park. When I heard on the news about a field hospital being constructed on the Van Cortlandt Park Parade Ground to aid in the COVID-19 hospitalization effort, I couldn't help but think that history was repeating itself. It's been just a little over a century since the Parade Ground last saw a mobilization of this magnitude. As a former Weekend Manager at Van Cortlandt House Museum, I also couldn't help but think about how much history has been witness by Van Cortlandt House over the last 270+ years. Formerly planting fields for the Van Cortlandt Family, the Parade Ground was developed in 1886 as a facility for the National Guard of New York. It quickly became a “home field” for the 71st Infantry Regiment for weekend drills and polo matches. Later, as the war in Europe escalated, the Guard put on a display of their military readiness in September of 1915. It wasn’t until the conflicts in Mexico in 1916 when the Parade Ground became a full-time National Guard operation. Mexican general and guerrilla leader Pancho Villa had been causing trouble on the Mexico/United States border, necessitating National Guard troops from New York to be sent west to protect the U.S. borderlands. The National Guard presence on the Parade Ground switched into high gear with the United States declaration of war on the Central Powers in Europe in April 1917. During this time, the National Guard became nationalized and thus could travel beyond the country’s borders. The entirety of the modern-day parade ground and north beyond the Henry Hudson Parkway (which had not yet been built) was transformed into a mobilization camp which could accommodate roughly six thousand troops. It included space to practice military maneuvers, a full mess set up, field hospitals, and a sea of canvas tents where soldiers prepared to be shipped off to Europe. National Guard troops from all over New York and beyond descended upon The Bronx. Due to its proximity to Broadway, Camp Van Cortlandt as it was known, became quite a spectacle for onlookers. After the spring of 1919, the Parade Ground once again became a place for the National Guard to do their weekend drills. During World War II, it would also be used as a training area, but not to the extent of what was witnessed during the Great War. After World War II, Van Cortlandt Park’s military history became a distant memory as baseball fields and cricket pitches were installed and cross-country runners began to dominate the fall months. As I ponder the news of a field hospital once again being built on Parade Ground, I can’t help but think that we are watching history repeat itself in our backyards. I’m choosing to remember those who created this space, a place for the greater good of New York, and saluting those who are to this day still working for the greater good of New York.

2 Comments

Reclaiming the Van Cortlandt Blind Earl Plates

This is the story of how 16 circa 1750 Royal Worcester Blind Earl plates were restored after a tragic fire at the home of their then owner, Miss Charlotte Van Cortlandt in Sharon, Connecticut. The story was told by Miss Van Cortlandt in 1959, 30 years after the experimental treatment saved the plates. Sadly we don't know the identity of the person who recorded the story who appears to be the potter Miss Van Cortlandt enlisted to try to save the plates. “As far as I (Miss Charlotte Van Cortlandt) can ascertain they belonged originally to my great-great-grandmother, Anne Van Cortlandt (Mrs. Henry White) who, with her husband, lived in the Van Cortlandt Museum House, New York, in Van Cortlandt Park. Eventually my father, Augustus Van Cortlandt, inherited them. After making Sharon, Connecticut our permanent home, the plates were packed in excelsior filled barrels and stored in the cellar. For many years, they had been the pride of my mother and we children had admired their bright colors when they were used on special occasions.” As collectors know, Blind Earl Plates were made at the factory at Worcester, England about 1746. The period known as the “Doctor Wall” period. The name which now characterizes them was given later because of the pleasure a certain unidentified blind Earl had derived from following the raised pattern on the plates with his fingers, the long leaf motif on the right, the bulbous rosebud balancing it on the left, and the serrated plate edge. In October of 1929 a fire destroyed the Van Cortlandt home in Sharon and the barrels in the cellar as well. For about three weeks the embers were too hot to make any investigation. Eventually the Blind Earl plates were salvaged. Fourteen Blind Earl plates were found unbroken and two more were cracked. Unfortunately, the color of the decoration on all of them was completely changed. Miss Van Cortlandt made a number of inquiries in different directions to find out if it were possible to regain the original colors on the plates and to remove the smoke stains on the white background. Finally, she consulted me as a Potter. “Can anything be done,” asked Miss Van Cortlandt, “to restore my Blind Earl Plates to their original color?” I looked at the dull, homely, discolored plate. The graceful rose-leaf that extended from one edge to the opposite was a dead liver color, and the small roses all grey. I recalled my own experience when my apartment in New York burned and though the furniture, pictures, pewter, and rugs were completely destroyed, there remained – unbroken but black – an exquisite Green Lykethos (6th Century B.C.) and a Copenhagen porcelain deer (20th Century A.D.). I left the Greek vase in its blackened state but I reclaimed the deer in my New York studio by submerging it for several days in a strong solution of soda ash, an ingredient that I use extensively in my glazes. This loosened the black which was a hard surface deposit of smoke and the deer was restored. So my first suggestion was to try the soda ash on the Blind Earl Plates. This we did unsuccessfully in my Sharon studio. No wonder. Why? Because the deer and the plate were not parallel cases ceramically. The deer was also porcelain, it is true, but the mineral color (very faint pastels) had been mixed into the feldspathic glaze and fired at a high temperature. All porcelain factories have their own clay composition and these are fired at various temperatures accordingly, but all true porcelain is fired very high. Blind Earl Plates were made of the famous clay of the Worcester Factory and glazed with a clear feldspathic glaze, then fired high. When cooled, the dead-white ware with its shiny surface and raised design was put in the stockroom ready for decorators. They painted the color on this raised design, adding individual motifs as the spirit moved. Special china decorating paints were used that contain minerals in their composition. Copper oxide is used for green, cobalt oxide for blue, manganese or iron oxide for all the warm or cools browns, etc. When this over-glaze, or china decorating, as it is called, was finished, plates were again placed in the kiln and fired, but at a very low temperature to develop the color and insure its permanence. In both the Van Cortlandt fire and mine, the heat was intense and in her case of long duration because of the well-filled coal bins, but it did not reach the porcelain temperature of the Worcester firing. Proof of this is that none of the plates was deformed as would have been the case if the heat had been as high as in the original firing. Fourteen came out of the house fire, flat and true. Also porcelain heat would have burned off all of the color except cobalt as most pigment cannot take high temperature. What happened is that in this smoky fire (wood, excelsior, coal, etc.) oxygen was cut off from the flame and in a smoky atmosphere flame removes oxygen from the color. Copper oxide will turn from green to liver color. The pinks and browns turn to grey or black. Sometimes the glazes containing iron oxide turn to the luscious green of the Sung celadon according to the glaze composition. By this deduction, I felt that re-firing the plates in a low temperature oxidizing kiln would restore them to the original gay greens Miss Van Cortlandt especially remembered. The technique of firing in a reducing (smoky) heat has been practiced for centuries chiefly by the Greeks, the Chinese, Indians, Koreans, and others. In my experiments for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I have fired various fragments of ancient pottery in both oxidizing and reducing kilns with interesting and satisfactory results. It was a great responsibility to re-fire these rare and otherwise perfect plates as I had never fired decorated china. What temperature should I choose? “Do anything that you like,” said Miss Van Cortlandt, “they are no good to me as they are!” I decided to try as a start, the low lustre heat. Nothing was added, no retouching by painting on the original plates. They were merely re-fired. The setting of the plate (I fired one at a time) in my small kiln was tricky. It was too big to set flat but I succeeded, after juggling, in setting it in a slanting upright position, not touching the walls of the kiln, and I placed a heat gauge, called a cone, beside it which I would watch through the spy hole. Once the kiln door is closed and the fire started, it is not opened until the firing is done and the kiln again cooled. While the heat, glows, color cannot be seen as you look through the spy-hole. The first was started and a careful record kept of the time for advancing the heat. The completed burning took about three hours. Then came a wait of twenty hours for the kiln to cool! Our excitement was intense as together we opened the kiln and viewed our results. There it stood, the color restored. Once more the large, graceful leaf was a singing, vibrant green, the stems a golden brown, and the roses a luscious pink. The whole plate fresh, happy, and lovely in color, the smoke stain gone from the gleaming white background, but the surface of the decoration was a little too dull and the plate needed a little higher fire to give the decoration more sheen. This we did, and both the color and the surface came out perfect. How did we know? By comparing it with one belonging to a member of the family in New York. Placing the two plates side by side the color seemed identical, surface and all. Subsequently, sixteen plates were re-fired, the excitement was always great, as each plate reappeared in its former glory.

Summer weather hit hard today in Kingsbridge inspiring me to post this archival photograph from a somewhat cooler day in the neighborhood. This photo shows the aftermath of an unanticipated Christmas blizzard in 1947. The team of snow-shovelers is shown working to clear the sidewalks around the Amalgamated Houses with what appears to be P.S. 95 in the background. Wouldn't a bit of that snow be a nice relief from today's steamy temperatures?

The Great Blizzard of 1947, according to Wikipedia, was a record-breaking snowfall that began on Christmas without prediction and brought the northeastern United States to a standstill. The snowstorm was described as the worst blizzard after 1888. The storm was not accompanied by high winds, but the snow fell silently and steadily. By the time it stopped on December 26, measurement of the snowfall reached 26.4 inches (67.1 cm) in Central Park in Manhattan. Meteorological records indicate that warm moisture arising from the Gulf Stream fed the storm’s energy when it encountered its cold air and greatly increased the precipitation. Automobiles and buses were stranded in the streets, subway service was halted, and parked vehicles initially buried by the snowfall were blocked further by packed mounds created by snow plows once they were able to begin operation. Once trains resumed running, they ran twelve hours late. Seventy-seven deaths are attributed to the blizzard. Drifts exceeded ten feet and finding places to place snow from plowing became problematic, creating snow piles that exceeded twelve feet. In Manhattan some of the snow was dumped into the sewers, where it melted in the warm waste water flowing to the rivers. When possible it was dumped directly into the Hudson River and the East River. Most suburban areas did not have such nearby alternatives to stacking the snow up. Low temperatures that winter led to the snowfall remaining on the ground until March of the next year.

|

Laura Myers, DirectorLaura has been the Director of Van Cortlandt House Museum since September of 1994. She is innately curious about many things and takes advantage of her Material Culture focus to explore more deeply the collections of Van Cortlandt House Museum. Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed