Slave Quarters

These attic rooms were studied by Dr. Bernard Herman of the University of Delaware in his examination and analysis of the house in February of 1994. The ell attic offers some of the most interesting insights into the social history of Van Cortlandt house. The unheated garret rooms with their board walls and original doors are built using wrought nails, a sign of mid-18th century construction. The plan of the north attic and the size of the individual rooms supports the idea that this space provided quarters for household servants. The practice of housing servants in unheated rooms tucked away in garrets is well documented in eighteenth and nineteenth-century houses throughout the region of the middle colonies including New York. The presence of such rooms in the Van Cortlandt House is significant not only for what they tell us about historic living conditions and differing lifestyles under a single roof but also for their remarkable state of preservation.

The room interpreted as slave quarters is adjacent to the back or service stairs from the second to attic floors in the Dining Room wing. The room is sparse with no decorative finishes, no heat, and no light other than what comes in through the door when it is open. There are two sets of broad shelves along the north and south walls which were most likely used as sleeping bunks. A third narrower shelf along the north wall may have been used by the occupants of the room for storing a few personal items. The beds are made with linen ticking mattresses stuffed with paper to simulate corn husks, a single coarse linen sheet, and a single wool blanket. Personal possessions include a madder red and indigo blue woolen Romal kerchief that would have been used either as a head wrap or folded into a triangle and worn over the shoulders to cover the bosom and a small strand of chevron glass African trade beads. A bunch of dried lavender has also been hung in the room as insect repellant and to help freshen the air of the windowless room.

Although we do not know which of the enslaved people owned by the Van Cortlandt family would have used this room as their sleeping quarters, it can be assumed that it was used by enslaved females working in the house although not the cook. It was most common for the cook to have slept in the kitchen which was originally in a separate building more or less where the Caretaker’s Cottage is located today.

The room interpreted as slave quarters is adjacent to the back or service stairs from the second to attic floors in the Dining Room wing. The room is sparse with no decorative finishes, no heat, and no light other than what comes in through the door when it is open. There are two sets of broad shelves along the north and south walls which were most likely used as sleeping bunks. A third narrower shelf along the north wall may have been used by the occupants of the room for storing a few personal items. The beds are made with linen ticking mattresses stuffed with paper to simulate corn husks, a single coarse linen sheet, and a single wool blanket. Personal possessions include a madder red and indigo blue woolen Romal kerchief that would have been used either as a head wrap or folded into a triangle and worn over the shoulders to cover the bosom and a small strand of chevron glass African trade beads. A bunch of dried lavender has also been hung in the room as insect repellant and to help freshen the air of the windowless room.

Although we do not know which of the enslaved people owned by the Van Cortlandt family would have used this room as their sleeping quarters, it can be assumed that it was used by enslaved females working in the house although not the cook. It was most common for the cook to have slept in the kitchen which was originally in a separate building more or less where the Caretaker’s Cottage is located today.

Enslaved People Who Worked and Lived on the Van Cortlandt Plantation

tThe first record of enslaved people living and working on the Van Cortlandt’s plantation occurs during Jacobus’ ownership, well before the house you are now standing in was built. The 1698 Census of Fordham and Adjacent Places lists enslaved people owned by Jacobus living and working on his land.

“hetter, tonne, marce, hester. antone the neger and dianna his wife and three children: ben, abraham, Jacob”

Other than this list of names, there is nothing more in the census to tell us the specific work these enslaved people did on the plantation.

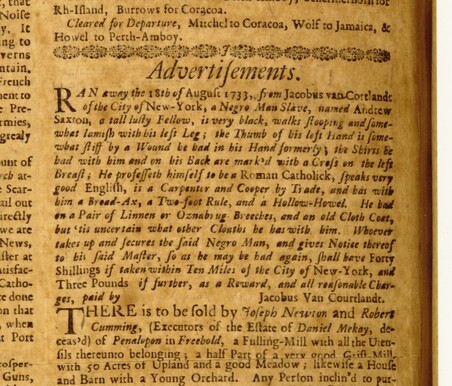

In addition to the enslaved people listed in the census as residents on the Van Cortlandt Plantation in Kingsbridge, Jacobus Van Cortlandt also owned Andrew Saxton who may have been a worker on the Yonkers plantation or at his brewery in New Amsterdam. Saxton ran away from Jacobus in August of 1733. A month later, having not returned on his own, Jacobus placed an advertisement for Andrew Saxton in the New York Gazette on September 17th, 1733.

“hetter, tonne, marce, hester. antone the neger and dianna his wife and three children: ben, abraham, Jacob”

Other than this list of names, there is nothing more in the census to tell us the specific work these enslaved people did on the plantation.

In addition to the enslaved people listed in the census as residents on the Van Cortlandt Plantation in Kingsbridge, Jacobus Van Cortlandt also owned Andrew Saxton who may have been a worker on the Yonkers plantation or at his brewery in New Amsterdam. Saxton ran away from Jacobus in August of 1733. A month later, having not returned on his own, Jacobus placed an advertisement for Andrew Saxton in the New York Gazette on September 17th, 1733.

“Ran away the 18th of August 1733, from Jacobus Van Cortlandt of the City of New York, a Negro Man Slave, named Andrew Saxton, a tall lusty Fellow, is very black, walks slooping and somewhat lamish with his left Leg; the Thumb of his left hand is somewhat still by a Wound he had in his Hand formerly; the shirts he had with him and on his Back are mark’d with a Cross on the left Breast; He professeth himself to be a Roman Catholick, speaks very good English, is a Carpenter and Cooper by Trade, and has with him a Broad-Ax, a Two-foot Rule, and a Hollow-Howel. He had on a Pair of Linnen or Oznabrug Breeches, and an old Cloth coat, but ‘tis uncertain what other Cloughs he has with him. Whoever takes up and secures the Said Negro Man, and gives Notice thereof to his Said Master, So as he may be had again, shall have Forty Shillings if taken within Ten Miles of the City of New York, and Three Pounds if further, as a Reward, and all reasonable Charges, paid by Jacobus Van Cortlandt.”

Regardless of whether Saxton was an enslaved worker on the Yonkers plantation or at the brewery, his specific trade as cooper or barrel maker was crucial for the storage and transportation of the products being manufactured by Saxton’s fellow workers.

Six years later, in 1739, Jacobus Van Cortlandt died in Bergen County, New Jersey. In his will he lists the following enslaved persons.

The enslaved people listed in Frederick’s will are:

What became of the enslaved people living and working on the Van Cortlandt plantation after the death of Augustus Van Cortlandt is not known. The staff of Van Cortlandt House Museum as well as local scholars from Manhattan College, Fordham University and The Kingsbridge Historical Society are continuing to research connections to the life and work of enslaved people on the plantation. As we learn more, we will share what we find with the public.

Six years later, in 1739, Jacobus Van Cortlandt died in Bergen County, New Jersey. In his will he lists the following enslaved persons.

- Pompey, identified as “my Indian man slave”

- Piero, identified as “my negro man slave”

- John, identified as “my negro man slave”

- Frank, identified as “my negro man slave”

- Hester, identified as “negro woman”

- Hannah, identified as “negro woman”

- Also unnamed, uncounted children, identified as the existing children of Hannah “Together with all their children that already are or hereafter shall be born of the body of the said negro woman Hester (except such of the said children as I may think fit in my lifetime to dispose of by deed of gift or otherwise)”

The enslaved people listed in Frederick’s will are:

- Mary, identified as Negro Girl Slave

- Hester, identified as Negro Girl Slave

- Levellie as Negro Man, the Boatman

- Piero, identified as the Miller

- Hester, wife of Piero

- Little Pieter, son of Piero and Hester

- Caesar, identified as Indian Man

- Kate, wife of Caesar

- Hannah, identified as Negro girl (left daughter Anne.)

- Saro, identified as Negro girl (left to daughter Eve.)

- Claus, identified as Negro boy (left to son Augustus.)

- Little Franke identified as Negro boy. (left to son Frederick.)

What became of the enslaved people living and working on the Van Cortlandt plantation after the death of Augustus Van Cortlandt is not known. The staff of Van Cortlandt House Museum as well as local scholars from Manhattan College, Fordham University and The Kingsbridge Historical Society are continuing to research connections to the life and work of enslaved people on the plantation. As we learn more, we will share what we find with the public.